Grandpa T was a giant of a man. Born in the first decade of the last century to pioneers of the Iron Range, it was inevitable that his life’s work would be based in the harvest and extraction of resources.

As a younger man he worked in various sawmills then found his way into the lumber camps. Hastily constructed, these camps were rough-hewn with roofs barely protected by flimsy tarpaper. Food stuff was nestled into root cellars with robust meals being prepared in a central cook shanty. Sleeping was dormitory style in crude log wall bunkhouses scattered about. Some of these short lived hell-on-wheels like enterprises were so hastily built and with such large gaps between the logs that when the cold winds blew in from the north, the centrally located wood stove could barely keep itself warm. It was common knowledge amongst the lumberjacks that the barns were the best built structures in camp, such was the value of the horses.

As the pristine stands of virgin timber were methodically harvested, the camps were hastily abandoned and the crews leap frogged forward to hew out a new camp, deeper into the new forest that was soon to be a new stump farm. Some of the camps bore the names of the titans whose fortunes they fed, names like Hatten’s, Roddis, and Scott & Howe. Others were so temporary and existed in such a whirlwind that no effort was put forth into names such as Camp 7. Such an unimaginative name was solely for reference and for the sheriff when he had ventured out to camp to serve out a warrant on a wanted man in hiding or recover the body of a fallen lumberjack. One perhaps mythical camp that certainly must have contained men of untethered libido, resorting to what was considered 100 years ago to be unthinkable behavior earned the dubious moniker of Cornhole Junction.

Despite the rough and tumble camp life and the back-breaking work, Grandpa T spoke fondly of the men and working life in the camps. He always had a team of horses, and both he and the team were paid a wage. On the days the horses were at rest, he would venture out with a double bit axe and carefully study then notch the tree for felling. Sawyers would follow behind and with their long bladed “misery whips”, complete the back cut, and the tree would fall.

Grandpa and Grandma T also had a side hustle as gyppo loggers. Together they would occasionally purchase tax deed “forties” from the county, harvest and market the timber, then peddle off the resultant stump farm. Grandpa T was proud that his family made it through the Great Depression without asking for relief or a handout.

By the middle of Grandpa T’s years, the virgin forests were largely gone. There must have been a moment of reckoning as that last crew raced towards the end of those forests and suddenly there were virgin forests no more. Perhaps Grandpa T had to walk away from the lumber camp back through the stump farm left in the wake. The trees would eventually grow back into some very nice second growth forests, but it would be a virgin forest no more.

He spent the rest of his working years in the iron and taconite mines but had very few colorful iron and taconite stories to tell.

Grandpa T often said that he never cut a live tree ever again after leaving the lumber camps. My brothers and I spent countless days with him harvesting firewood in his 120-acre forest and can attest to that. He carefully navigated the farm tractor or snowmobile about, never damaging or scarring a tree and being ever mindful of creating ruts. Windfalls, lightning strikes, and blowdowns were carefully sawn up and the brush neatly stacked. A much-favored firewood source were the small diameter maples that had lost the race to the canopy and were starved of sunlight by the victors. “Rampikes,” he called them, and their trunks devoid of bark and branches resembled long bleached bones growing out of the ground. At the end of his life the 120 acres or rolling hills and flinty bluffs contained a pristine and healthy stand of quality maple, all made possible by meticulous stewardship and that surely made Mother Nature proud.

Atonement.

A giant man, Grandpa T’s imposing stature was only exceeded by the size of his heart. He loved his children and grandchildren and greatgrandchildren deeply and would do anything for any of us. Indeed, his guidance and generosity were life changing. Still, while he was alive there was this feeling that perhaps he didn’t really understand his distracted grandson who would look at a deer rather than eat it, and that grandson probably didn’t really understand him that well either.

I spent the better part of a decade working in the oilfields. The first two years were in the Alaskan Arctic as support staff constructing work camps and maintaining them. The monthly commute to work consisted of a flight seated in the back of a combi-cargo plane over the pristine tundra dotted with arctic polygons. As the flight neared Deadhorse, the virgin tundra morphed into the dizzying tentacles of a vast network of pipelines and production facilities. During the sunless arctic winter, the greasy auburn flames of the flares burning off hydrogen sulfide and natural gas cast an ominous glow onto the otherwise dark horizons.

But I felt no guilt. I was not the driller, was not tripping casing, was not doing wireline or coil tubing, was not constructing pipelines. I was support staff. And those big fat oil field paychecks sure bought a lot of groceries. I played a tiny part in providing habitat for humans in an inhospitable environment.

Subsequent oil field employment in the Lower 48 transitioned from support to well service. Untold tanker loads of fresh water were dumped into the ever thirsty frack batteries. When there were not enough semi tractors and tankers in existence to feed enough fresh water to the insatiable fracking operations, temporary soft pipelines, miles long were run, fed by pumps that sucked out aquifers 24/7 but could never quite fill the massive Poseidon tanks that replaced the frack batteries. I became a bulker, then a pressure pump operator feeding the grout that entombed steel casing that plunged miles deep into the earth. It was my job to go up on the rig floor and stab the head at the beginning of the pump job and then at the end, bust off the head with its accompanying dramatic geyser of grimy invert fluid. As a personal choice and for moral reasons, I never actually worked as a part of a frack crew but was now doing the dirty work none-the-less.

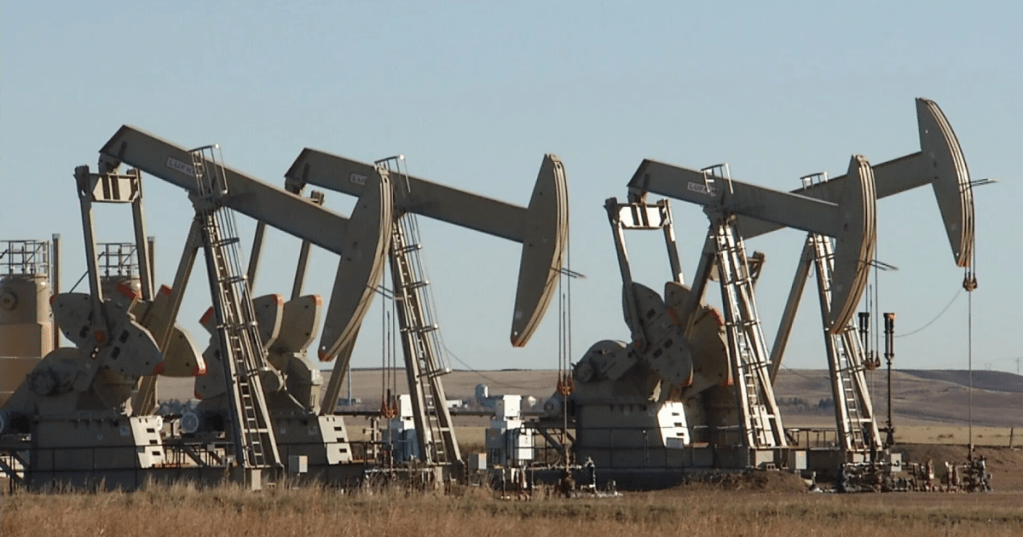

There was not a lot of guilt about doing such work in a place like the oil patches of Texas, as I had never seen Texas before there were oil wells in Texas. In my mind, Texas always had oil wells and always would. But Colorado, Montana, and North Dakota were different. In wonderings through the Bakken Patch in the 1980’s, a pumpjack was somewhat of an oddity. But suddenly years later wells and the accompanying pump jacks were proliferating at an astonishing rate.

My last oil field service job was in the Little Missouri Breaks, a truly beautiful place. As our work convoy climbed up out of this once pristine upside-down mountain and out onto the stark plains, the extent of it all struck me. It was now all just another oilfield. But those big fat oil field paychecks sure bought a lot of groceries. And I suddenly realized exactly why Grandpa T never cut another live tree. I played a very tiny but none-the-less active part in turning a rather unique portion of the American West into an industrial wasteland and could not simply rectify that as just being support staff.

Eventually simple economics will clean up the Bakken somewhat. The cast off and rusting equipment will go to scrap, the temporary work camps will vanish, the stacked-up drill rigs will relocate to another patch, the piles of well and pipeline casing will be buried in the ground or sent elsewhere. The traffic will ease, the rough necks and prostitutes and company men will move on to the next dirty bonanza. Eventually, the only sign that we were ever there will be the myriad of pumpjacks spread out from horizon to horizon, lazily drawing sequestered carbon to the surface. But there will never be that same pristine Little Missouri Breaks ever again.

That was then and here I am now, starting a new life out in the woods.

The lifetime passion project of a local trail boss includes caring for the nearby recreational trails, and he stopped by for a tour of my cabin. He eyed an old photo hanging on a beam. It was of Grandpa T wearing a wry smile and a jaunty Indiana Jones like hat, double bit axe over his shoulder; a misery whip sawyer and another notcher were beside him, the cook shanty of Hatten’s Camp in the background. While I shared this story the trail boss listened intently, nodding and studying the photo.

He later named a new trail near my cabin “Vernerin Kulku”, Finnish for Verner’s Traverse, to honor my Grandpa Verner Thompson.

The naming of that trail really brought the wagons full circle. We all do what we need to do to afford a bag of groceries and usually think little of the larger consequences. We can’t undo the past. But I hope to be as good a steward to my little patch of land as Grandpa T was to his 120 acres.

Atonement.

Previous Posts:

Very good Ger, I hope that Grandpa and Grandma T will get this “up there”! They’d both be proud.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have Grandpa stories to tell you that Mom told me- his 1st team, the renegade team & the bear. In that photo, he’s holding a jar of pigs feet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow , great job. I’m officially a follower.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic, Gerry! So lovin’ this blog! I remember your Grandpa. He was a much beloved man.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a fantastic writer. Enjoy all of your blogs. Keep writing!!

LikeLiked by 1 person